Prison Design for Life, Not Life Sentences

Steen Gissel, architect of Norway’s Halden Prison discusses the tension between security and humanity.

Steen Gissel, architect of Norway’s Halden Prison discusses the tension between security and humanity

Halden sits in Southern Norway near the Swedish border boasting pine forests, wild berry picking, a popular summer concert series—and the world’s most humane prison.

Reputed as such because of Norway’s belief in “the normality principle,” life at Halden—opened in 2010—is meant to emulate life on the outside as closely as possible, all while operating as a maximum-security prison. If form follows function, as the design adage goes, then the function of Halden balances security with humanity. And its form is built from an underlying belief that confinement is punishment enough and no further environmental punishement should be applied.

In the wake of renewed advocacy and social justice reform, correctional officers from prisons in Oregon, California, North Dakota, Pennsylvania and more are looking to Halden as a model for how to restructure their own carceral environments.

Steen Gissel, architect at Danish firm ERIK arkitekter, who designed Halden Prison in collaboration with Norwegian firm HLM, video-conferenced in from his studio in Copenhagen to discuss Scandinavia’s philosophy on incarceration and how, despite becoming globally renowned for its humane practices, Halden is still at its core, a prison.

Question:

Halden Prison balances maximum freedom within an environment of maximum security. What kind of tension did that create in the design process?

Gissel:

You often see prisons that are more or less in one big building because that's logistically much easier. [Halden] is more of a campus design, [which is] a logistical nightmare. Every time an inmate has to go from A to B, someone will either have to follow them or they have to go through the [metal] detectors. There will be cameras everywhere. [The Norwegian Department of Justice] wanted the normality of living in one building and going to work or going to school in another building. That was a very deliberate choice that they made. And they knew exactly what they were doing. You end up in this architectural version of the uncanny valley.

Question:

I’m not familiar with the uncanny valley reference. What is that?

Gissel:

Uncanny valley is [a concept from] people that work with robot design. If a humanoid robot is made from glossy white plastic, you're fine with it. If it looks exactly like a human, you would be fine with it. But if it looks close, but not quite, it becomes creepy.

The prison does look kind of like a university campus in the pictures but when you get up close to a window, you can see how thick the glass is. You get close to a door and you can see that's a pretty substantial steel door frame. And that becomes kind of strange. You are definitely very much aware this is not a dorm room. Certainly not a dorm room that I would like to live in.

Question:

You’re saying that despite the sleek design, you never forget that you're in prison…

Gissel:

Not for a single second.

Everything is bolted down. Everything is designed so that you cannot attach anything to it. Shower heads are integrated into the walls. You cannot hang yourself from the shower head, which is one of the things you have to take into consideration when designing prisons. Doors open out of the room so that they are harder to barricade. It may look like it comes out of an IKEA catalog, but I can assure you it doesn't.

And then there is the whole regime thing. I mean, you are confined to ten rooms and one kitchen, and every time you want to go from A to B you go through the metal detectors and all that. It will never be like living in a normal dorm room.

Question:

This campus-style prison—as a manifestation of the normality principle—was a priority for the Norwegians, even at significant financial cost. What drives this philosophy?

Gissel:

[In] many places around the world, you can be sentenced to life. That is not a possibility in Norway. If we sentence people to life, there's the mindset that, okay, we just lock them up and throw away the key. If it's 21 [years, the maximum sentence in Norway], well then we better start resocializing or educating or doing something.

Question:

So this informs how people are cared for in the wholeness of their lives behind bars?

Gissel:

Only we don't have a single bar anywhere.

Question:

Touché. I’m glad you brought that up. No bars. And the windows are quite large—why was this a priority?

Gissel:

You wanna give people the possibility to open a window because that gives you a feeling of having control of your own environment. It's just a flap with, like a grate behind it. You can open it all the way, but you can't even stick your hand out. It would actually be nice to have bars in front of the windows so that you could properly open [them]—but that kind of sends the wrong signal.

Halden makes use of cork and wood materials that help absorb sound, a contrast to traditional prison materiality of concrete, linoleum, and steel, seen across the United States, which amplify sound (Vox), and by effect, stress, discomfort, and poor health (U.S. Department of Justice).

Question:

This was your first prison design—what surprised you along the way?

Gissel:

You spend your whole education learning how to do things so they are pleasing. And then suddenly you have to do the exact opposite. That was quite a steep learning curve. And [it was] depressing. You learn about all the horrible things [like] having to design a shower head so that people won't hang themselves.

We got these risk assessment reports every couple of months [where we’d learn] that now, the risk of an inmate locking himself up in his room and setting fire to himself has gone up by 12%. That was probably the weirdest kind of feedback I've ever had as an architect.

Question:

The philosophy guiding Halden sounds a lot like the social determinants of health here in the US, with a priority on education, physical environment, employment, and social support networks. How much was health and wellbeing part of the design conversation?

Gissel:

I don't really recall talking about health back then when we were doing the project, but it's obvious that if you treat people humanely, that is a healthier way of living. Maybe the client was aware of that, but we didn't focus on it at all. It was more about the philosophy of what the punishment is supposed to be: it's just incarceration and everything else should be as normal as possible.

Question:

Incarceration is very much a community issue, in that the experiences imprinted on a person working at or visiting a prison carries into the community. How did you think about designing for non-prisoners who use the space?

Gissel:

If you create an inhumane environment for the inmates, you also create an inhumane environment for the staff. If you create visitation facilities that are horrible, you end up punishing some nine-year-old girl visiting her dad. Is that reasonable? She didn't kill anyone… I presume.

Question:

There is a significant social incentive to treat people well while they’re in prison, so they come out well—and the built environment can support this. Does it work

Gissel:

Norway has one of the lowest recidivism rates anywhere in the world. So we know that this system works.

You have to think about what is it that you want. Do you want to satisfy your own need for punishing this person? Or would you like to live in a society with a lower crime rate?

#

Interview edited for length and clarity.

The Death Row You Haven’t Heard Of

For the thousands of prisoners who die in custody in the United States every year, life ends in basically one of two places: in hospice or in a cell.

Where California’s Prisoners Receive Humane End Of Life Care

For the thousands of prisoners who die in custody in the United States every year, life ends in basically one of two places: in a cell or in hospice. The former is most common, because the latter is extremely limited. The US has about 2,000 prisons, but only 75 in-prison hospice programs.

This disparity can be explained by simple supply and demand: prisoners are getting older while qualified staff are harder to come by, said Lisa Deal, executive director of the Humane Prison Hospice Project, whose organization trains prisoners to be hospice caregivers in a peer-to-peer support model. In order to be sustainable though, programs also need administrative buy-in at the highest level.

California Medical Facility in Vacaville, California holds one such program. Founded in response to the AIDS epidemic in 1996, it is the oldest prison hospice care program in the US. There are seventeen hospice beds at CMF, six of which are in private rooms, along a wall referred to as “death row” where patients go to actually pass away, said Fernando Murillo, who was previously incarcerated within CMF’s broader system.

Prison hospice programs typically offer peer support, chaplains, and medical services for prisoners in the last six months of their life, but what makes CMF unique is the culture shift they’ve been able to achieve.

For Murillo, there was a marked shift when he walked into X Corridor, a “pristine, white, very well-manicured, angelic” hallway, and towards the hospice center. Murillo spent the final five years of his 20-year-sentence working as a hospice caregiver, and said that when he crossed that threshold into the care facility, the hierarchies and power structures that dictate prison life dissipated. Patients and staff alike “don’t feel like they’re in prison anymore. Their humanity is prioritized,” he said.

“Normal” is the goal, said Dr. Michele DiTomas, Medical Director at CMF. “Patients are free [within the hospice facility], there are no locks on the doors. They can walk up to the nursing station, they can chat with each other, they can chat with the doctors, they can step out into the garden, they can go watch TV, they can do a puzzle with their friends.”

Caring for a dying prisoner isn’t all that different from caring for a dying free person. Over the years Murillo was trained in basic nursing functions like taking vitals, turning a patient to avoid bed sores, or changing their diapers or wound dressings. Beyond the technical stuff, he said, “what I primarily did every day was just offer my humanity to somebody that was in the most vulnerable state.

Hospice patients are open about their lives in a way prisoners usually are not, said Murillo, and veterans often share about their experiences in combat for the first time in their lives. Some of their stories are entertaining, others horrifying, he said. One of his friends—a hospice patient and veteran—told him about the worst acts of war violence he’d been in, sharing that in the midst of it, he saw “a tiger, you know, this beautiful, majestic animal, [that] appears in one of the ugliest events that humanity could possibly perpetuate.”

About 60-70 prisoners die in CMF hospice each year, said Dr. DiTomas. Each receives a memorial service where it’s not uncommon to have a line of friends waiting to share stories of the deceased. Veterans receive “the whole flag-folding ceremony to really honor their service as well,” she said.

Both Murillo and Dr. DiTomas agree that nurturing an environment of dignity and humanity for people at their most vulnerable moments is why the hospice program at CMF is so valued. That, and how cost effective the program is, said Dr. DiTomas. She described what it would look like if the program did not meet their patient’s needs. “They become stressed,” she said. “Somebody's oxygen saturation is dropping, [then] we put ‘em in an ambulance and send them to the emergency room. Not only do we incur a lot of costs from the ambulance and the custodial support and the acute care hospital and possibly the 14-day [intensive care unit] visit that the patient didn't want, but we haven't met the patient's needs either. So hospice not only gives the patient what he wants, [but] it's extremely fiscally responsible.”

Dying in hospice care also spares cellmates one of the worst events they can experience in prison, said Deal. When a prisoner dies in his cell, their cellmate is sent to solitary confinement while an investigation is conducted into the nature of the death. This is traumatic, says Deal, because cellmates can become very close, and often one will care for the other in their declining health.

“Can you imagine losing [the equivalent of] a family member and then instead of getting support for your own grief, you're sent to solitary confinement?” said Deal. “It's just horrible.”

Both medically and socially, hospice programs offer critical support to prisoners. For those who die in a cell they receive no morphine for pain management, for example. For those who die in the general prison infirmary, they are stripped of the social support they might receive in the community of their cell block or within a specialized hospice environment.

Dr. DiTomas recognizes that the carceral system was not designed with the dying in mind, which makes the role and presence of her team all the more valuable. It is a special skill set, she said, to navigate the complicated system of prison security protocols in order to bring about last wishes for her patients, whether it’s navigating the courts for compassionate release, tracking down long-lost family members, or arranging final goodbyes. In one instance, “we found their family in 24 hours when other places had been trying to do it for months.”

One goodbye was especially moving due to the unique circumstance of a dying father wishing to connect with his daughter, both of whom were incarcerated, but at separate California facilities. This was not an easy phone call to arrange.

“Our warden [is] used to us pushing the boundaries,” said Dr. DiTomas. And it paid off. The daughter was able to say goodbye to her father, albeit at a physical distance, over a 15-minute phone call, and was offered grief counseling.

“There can be some moral injury when everybody can see that [arranging the call is] probably the right thing to do, but people didn't necessarily feel empowered to make it happen. [But] by showing people that you can make that happen, hopefully… it's a culture change mechanism as well,” said Dr. DiTomas.

Few people would choose to die in prison, said Earlonne Woods, a former prisoner of California’s carceral system and host of Ear Hustle, a podcast founded by Woods during his time at San Quentin, during a live recording in Portland, Oregon. But compassionate release is difficult to arrange—patients must have somewhere to be released to, and it’s not guaranteed that family members are willing or able to take them in, said Deal. Care facilities, also, may be reluctant to accept a former prisoner.

Woods said some prisoners talk as if their freedom from prison will come before their freedom from this life. It won’t, he said, yet their peers will indulge this final form of wishful thinking.

There are organizations that act as a bridge between the supply of community hospice beds and the demand for them, like Missionaries of Charity, a California-based organization that alerts CMF of open beds at facilities that accept the formerly incarcerated, such as Gift of Love in Pacifica. But even if all the aforementioned arrangements go well, the paperwork has been known to take longer than the person has left to live.

“Death is a great equalizer,” said Murillo, “and I notice in this space that people are constantly having their consciousness challenged.”

Murillo has been out of prison since November 2020 and works at a Bay Area organization focused on changing prison culture through community health principles.

Under Dr. DiTomas’s leadership, the best practices established at CMF’s hospice program are making their way into other California carceral facilities. Her vision for the future, she said, is that everyone with an illness in prison—not only those in hospice—would receive the benefit of peer support and a companion to help them out.

#

How Not to Deliver Mental Health Care in Prison

Prisoners are routinely let down by the very systems whose care they are entrusted to. Yet the five men interviewed for this story all served time, struggled with their mental health, and found healing despite the failures of the carceral system.

Stories of Healing and Resilience

When Craig Stanland’s depression deepened to the point his suicidal ideation became actual planmaking, he knew he needed help. Stanland was incarcerated in upstate New York at Otisville Federal Prison Camp from August 2014 to November 2015 where, when he reached out to a psychiatrist, she handed him a flier titled, “Stress Management Strategies.” On it were tips like “have a relaxing bath,” “give yourself treats,” and even physical activity recommendations like chop wood or go swimming.

“We did not have a swimming pool,” Stanland said. “So I saw that [paper] and I felt it was like putting a bow on the fact that [to the psychiatrist] I was a nuisance.”

This advice, as it turns out, was published by a husband and wife doctor team in the UK who work for Interhealth, an organization that works with aid workers, not prisoners. Stanland is not sure how their advice sheet ended up at Otisville, but admits, “there's good stuff in here, minus the context of somebody being in prison.”

This mismatch between his expectation of help and the contextually-inappropriate care he was offered is echoed in prisons across the United States. “Prison is an acute stressor,” said Dr. Nicole Jackson, who is the Director of Autopsy and After Death Services at UW Medicine. “As soon as you enter, your health plummets—and it's chronic, so that stress is ongoing.”

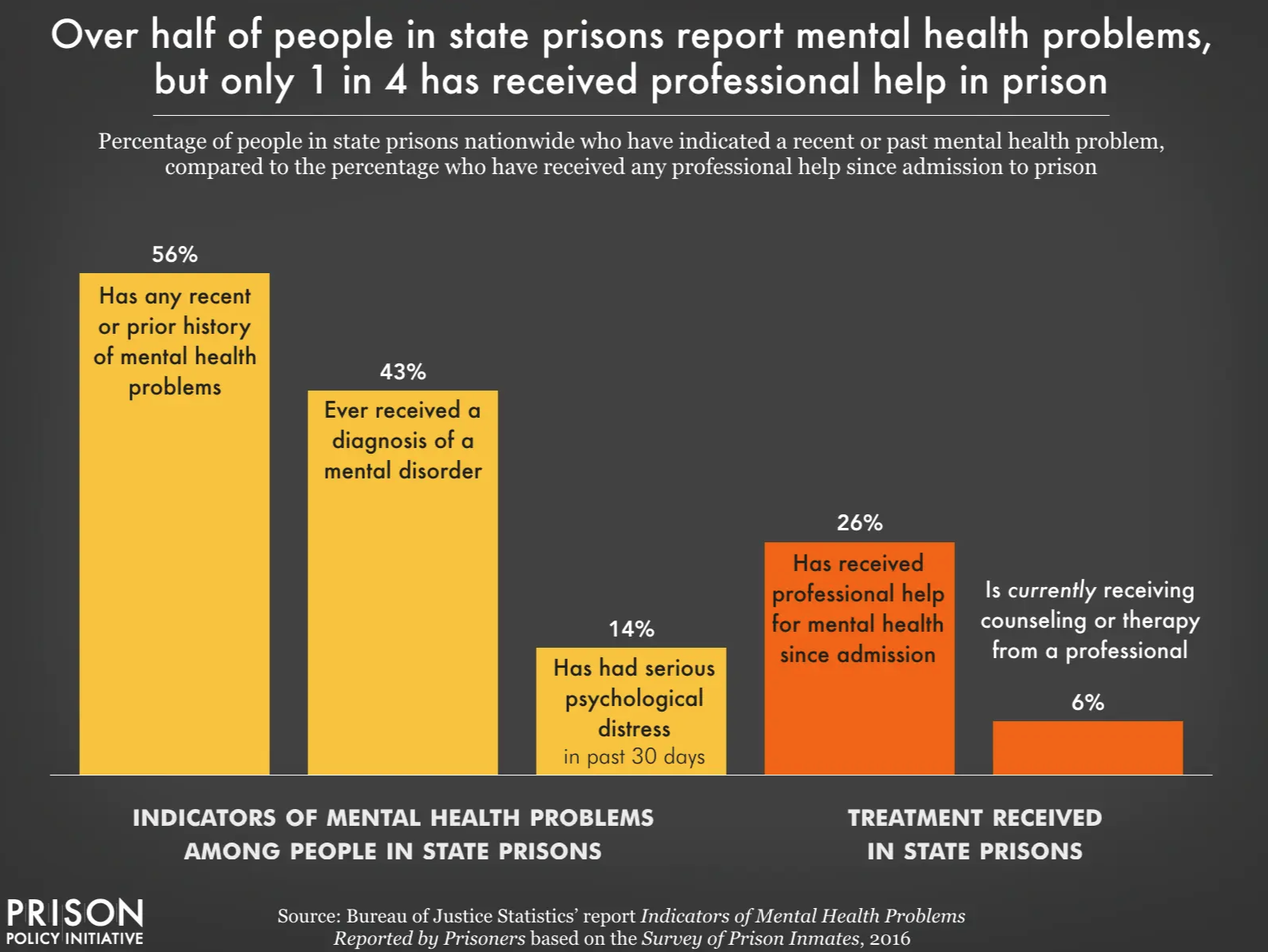

Over half of people incarcerated in state prisons suffer from a mental health condition, according to the Prison Policy Institute's reporting of the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ 2016 Survey of Prison Inmates (the most up to date data available). Yet only a quarter of prisoners report having received help. Six percent were currently receiving mental health care.

Prisoners are routinely let down by the very systems whose care they are entrusted to. While prisoners are the only group whose healthcare is constitutionally mandated—via the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the 8th Amendment—barriers to accessing that care are all too common, from appointment delays to lack of believability and outright negligence. In the absence of suitable, prison administered care pathways, many patients have developed their own coping mechanisms or tapped into holistic forms of care.

As a healing modality, yoga and meditation, for instance, makes a lot of sense to Oneika Mays, who taught an integrated practice of care at Rikers Island in New York for over a decade. Her teaching philosophy is tailored to the unique conditions of a carceral environment, she said. Yoga “is about this idea of connecting ourselves with the world around us and being able to calm the chatter that's in our minds, and using practices that are wrapped in unconditional friendliness. If that's not trauma informed, I don't know what is,” she said.

The five men featured here all served time, struggled with their mental health, and found healing despite the failures of the carceral system.

Craig Stanland

Incarcerated from August 2014-November 2015 in New York

Imprisonment meant losing his career, income, homes, and marriage, but worst of all, he said, he also lost his sense of self. “I was alone at rock bottom with the man who was responsible for this. And I loathed that man.” Stanland had begun to plan his own suicide when a friend came to visit him. His friend had driven over two hours to spend time together, a show of support that helped Stanland understand he is more than his mistakes. He was valued, and believing this helped him cope with his remaining time in prison. “I didn't even know that gratitude practice was a thing. I just sat down one day. The sunrise was absolutely stunning. And I wrote, I'm grateful I’m alive to see this morning.”

Beto Contreras

Incarcerated from 1991-2002, 2002-2006, 2009-2011, 2011-2013, 2013-2016 in Wisconsin

“What I've learned about the system is no matter where you're at, they pass out pills.” Contreras grew up in foster care and went to prison the first time at 16. He spent 23 years locked up, nearly a third of them in solitary confinement. On his seventh visit to solitary, something inside him shifted. “I was just so mad. I was like, “dude, you can't even be in population. You're in the hole again.” I looked in the mirror, and I really was sick with what I saw.” From that moment, he changed. He began working out with different people. He stayed out of highly-charged conversations and attended a group-style cognitive intervention program that helped course correct his internal dialogue. These efforts strengthened his spiritual connection to his mental health, something he has maintained since getting out. “It was hard,” he said. “But I did it.”

Colt White

Incarcerated since 2015 in Idaho, Texas, and Arizona

It’s not uncommon for prisoners to be moved from facility to facility, but White has also been moved from state to state—three times—effectively isolating him from everything he’d once known. While told the moves were due to his good behavior, he felt punished, and his resentment ate away at him. In Idaho, he had enjoyed working in a prison program that trains dogs. It gave him purpose. When he was transferred to a Texas prison that did not have a dog program, he was able to start one. Working with the dogs “shifted everything for me.” He said it’s scientifically established that “having a dog will lower your anxiety and decrease your blood pressure. It’s really healthy to have an animal.”

Mason Suehs

Incarcerated from 2008-2009 and 2017-2018 in Oregon

Suehs estimates he’s taken over thirty anxiety medications, usually two or three at once. “I felt like I was in a battle, you know, fighting my anxiousness all the time.” Other methods of relief seeking included meditating for two hours every day, not leaving his house, and reading self-help books. Still, he wound up in prison two separate times. One day during his second stint he heard other prisoners talking about The Insight Alliance, an outside organization that ran guided group meetings in the facility. The group’s underlying philosophy was just what Suehs needed to hear: you’re not broken. Thanks to the group, Suehs now sees his feelings as a kind of mental storm that flows through him rather than batters him. He doesn’t need to react or attach himself to every emotion. Today Suehs is a free man, off anxiety medication entirely, and returns to prison each week to lead the very meetings that changed his life.

Eric Clark

Incarcerated from 1992-2020 in California

Clark had so fully embodied the hardened criminal persona that he had to relearn how to smile, he said. His cheeks were sore for days. In Calipatria State Prison, in Southern California near the New Mexico border where Clark spent 14 years, mental health was highly stigmatized. People who displayed symptoms of conditions like ADHD or schizophrenia were considered weak—prey—and were beaten or even stabbed. This culture was exacerbated by the prison’s isolation both in geography and also from outside services—services like Boundless Freedom Project, for example, that offers meditation and yoga to some of California’s 34 correctional facilities. Clark’s first yoga class came much later, after he transferred to a new prison up north near Sacramento, a region with resources. He’d had hip pain due to nerve damage and a new doctor he was seeing, an Indian man, said he’s seen it before but the answer didn’t lie in Western medicine. The doctor told him to try yoga. Within a month, Clark could walk without a limp again, but it was the mind-body connection forming that really transformed him. “One of the things that yoga was doing was helping these brawny prison guys who thought all these muscles meant something learn that we were off balance between [the mind] and the rest of our bodies.” Yoga gave Clark clarity and helped him to understand he could make choices of his own volition, rather than what had always been prescribed to him by the culture he was subjected to. Today he works for the Boundless Freedom Project as a program administrator.

In sharing their experiences with what worked for their mental health and what didn’t, Stanland, Contreras, Suehs, White, and Clark are a representation of the knowledge and wisdom that could inform and reform mental health care services in prison. When formal systems fail the people they are purported to serve, those people suffer. The lesson then becomes, simply, to listen to those who’ve lived it.

#

Diabetes Management No Match For Carceral Conditions

When Steve Brooks was diagnosed with prediabetes in November 2021, his physician put him on the tried-and-true care plan: reduce unhealthy foods, increase exercise. But he faces an insurmountable barrier: his address.

When Steve Brooks was diagnosed with prediabetes in November 2021, he found himself uniquely incapable of reversing his condition. His physician put him on the tried-and-true care plan: reduce unhealthy foods and increase exercise. But he faces an insurmountable barrier—his address.

Brooks is serving a life sentence in San Quentin State Penitentiary for violent crimes he committed as a young man. At 50 years old, he’s been in prison longer than he hasn’t, and for the last six has been at California’s penitentiary by the Bay. San Quentin is the state’s oldest, opened in 1852.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Brooks considered himself to be a healthy man. He cares about his health, he works out—San Quentin has a running club he’s a member of—and stays informed about the latest preventative and testing guidelines for his age group. None of this prepared him for how the lifestyle of lockdown would become a health threat.

Brooks—like many people across the world—was forced into a sedentary lifestyle. His regular running workouts were cancelled and meal routines were reconfigured to accomodate social distancing where possible. When the rates of infection were at their highest, the kitchen at San Quentin was shut down entirely and an outside vendor provided meals to over 3,126 prisoners. Brooks said it was “actually some great food. Everybody loved it.” They loved it so much, he said, that he and his fellow prisoners didn’t want to waste the opportunity; he ate more than he usually would have. “That contributed to these extra calories and extra pounds that we started to develop.”

Diabetes affects the body’s natural ability to process glucose. In a non-diabetic body, insulin is secreted by the pancreas and processes glucose. In a diabetic body, insulin production is stunted and glucose levels spike and wane, events that can be deadly without intervention. Insulin is required from a pump, pill, or injections, multiple times a day. This becomes routine for diabetics, but, Brooks said, he fights everyday to avoid it.

Diabetes is not uncommon in prison. Reporting from 2011 shows that 4.8% of the prison population has diabetes. This is less than half the average for diabetes on across the country, at 11.3%, but one major difference is how it's handled—and the San Quentin living conditions had become the precursor for Brooks’ prediabetes to take hold.

Prediabetes is a reversible condition—which is good news for the 38% of Americans who have it—but only for those with the knowledge and freedom to make the necessary changes to diet, exercise, and lifestyle. In October 2022, San Quentin launched a diabetes education and peer-support group, and while Brooks has yet to attend, he is hopeful about its impact. In the meantime, he navigates the diet provided to him, which often includes a carbohydrate-heavy rotation of waffles, breads, and cakes.

The “Prisoner Diabetes Handbook”—for prisoners, by prisoners—recommends simply abstaining from unhealthy foods. They focus on mental strength and food rationing in lieu of meals that are actually healthy. Brooks agreed that this is the only way to manage his condition for now, but notes that abstaining from food leads to hunger later because there are no healthier substitutes available either in the kitchen or in commissary.

With lockdowns lifting, Brooks did begin training again—though not in earnest because his own bout with COVID-19 left his lungs weak and asthma exacerbated. In his cell, all 49 square feet of it which he shares with another man, “you might have enough space to do a pushup,” he said. “But it's gonna be an awkward pushup.”

Brooks’ blood sugar levels are tested every three months, and so far, he said, every test has shown no improvement. If Brooks isn’t able to roll back his prediabetes, his condition will worsen. According to the CDC, it can take ten years for prediabetes to become Type II diabetes, which is where Brooks’ health is heading without appropriate intervention.

#

The Economies of Care Rising out of Prison’s Structural Violence

California law requires any menstruating person in custody be provided with menstrual products upon request—but in prison, a legal mandate cannot guarantee accessibility.

Restitution At California’s Women’s Prisons, Social Suffering, And The Rise Of Informal Economics Of Care

For the 3,714 women incarcerated in California’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) (“Weekly Report of Population,” 2023), the economic conditions forced upon them behind bars create personal budgeting challenges and health hardships that, by effect, also lead to informal economies of sharing and caring. While some of these economic barriers to health have been eliminated in recent years, the true solution must be one that is holistic in nature rather than piecemealed.

There are large financial forces at play when it comes to prison (the Prison Industrial Complex) (Davis, 2003), but those most acutely felt on a day-to-day basis by the incarcerated include the effects of high rates of restitution paired with low working wages. Together they represent structural violence and create conditions for social suffering, especially for women and their unique health and health care experiences.

Restitution

Restitution is an amount a person pays to the state as penalty for the crime they’ve committed. It is ordered by a judge, paid to a third-party board, and ranges from $300-$10,000. The stated goal of restitution is to “pay back the damage caused, both to the state and to the victim(s)” (Offender Restitution Information - Office of Victim and Survivor Rights and Services (OVSRS), 2022), a definition that both emphasizes blame, economic punishment, and runs counter to an understanding of social health which acknowledges that violence enacted by individuals is often a product of systemic and social failings forced upon them since— and even before—their birth. Perpetrators of crimes are often themselves victims of social shortcomings (Western, 2015) and the act of requiring them to financially contribute to a system that has failed them so greatly is its own unique form of gaslighting.

In California, the carceral restitution rate is 50% and it applies to all money earned in prison through a work program and all money gifted to an incarcerated person from a friend or family member (Offender Restitution Information - Office of Victim and Survivor Rights and Services (OVSRS), 2022). The percentage is high, up from 22% in 2001, but not as high as some people who are advocating for a 75% restitution rate, would like (Jane Dorotik, personal communication, April 25, 2023).

Restitution has an effect inside prison much like a tax would have for people on the outside, except that the alleged associated social services that are supposed to come along with it, don’t exist. Instead, it contributes to the economic marginalization of a population already suffering from multiple money-related comorbidities.

Wages

In prison, every penny earned is valuable because there’s not much of it and it’s not easy to earn. Some US states don’t pay their prison laborers at all (How Much Do Incarcerated People Earn in Each State?, 2017). Where unpaid prison labor still exists, it does so due to a loophole in the 13th amendment which made slavery illegal except when used as punishment for a crime (13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Abolition of Slavery (1865), 2022). By this standard, California stands out as a state that does pay for prison labor (even though it is not yet constitutionally mandated; voters continue to be split on this issue (Lyons, 2022)) at eight-to-thirty seven cents an hour (Prison Wages: Appendix, n.d.).

To put this math equation into perspective, it would take a person imprisoned in California’s system over 137 years of full time work—35 hours a week, for all 52 years a year—at the minimum wage of eight cents an hour, fined for restitution at 50%, to pay back the maximum restitution amount of $10,000. Restitution debts follow people even after they are released from prison where, on the outside, they face other economic barriers to both financial and bodily health (Offender Restitution Information - Office of Victim and Survivor Rights and Services (OVSRS), 2022).

In these ways, high restitution and low wages, as a matter of policy, become the structural forces that determine the wealth and health of a population. It does so not only at the expense of the affected population, but also for the benefit of decision makers. In lieu of being forced to pay prisoners even a standard California minimum wage of $15.50 (Minimum Wage Frequently Asked Questions, n.d.), they can continue to keep other budgets operating within the status quo.

The amount of money a person is left with after restitution is not much (using the formulation above, a person could expect to bring in $6.40-$29.60 monthly), and yet it is expected to pay for commissary (food, especially to augment poor cafeteria options), necessities (such as deodorant), and even a little bit of fun (like beauty supplies). Whether from the lack of money itself or the circumstances that these economic conditions create, the results manifest as limited choices, increased isolation, humiliation, and poor health experiences for women in California prisons.

Health Consequences: Menstruation

One of the ways these forces manifest is through menstrual cycles. California law requires any menstruating person in custody to be provided menstrual products upon request. It is one of 22 states that offers such legal protections (State Laws Around Access, n.d.), but even a legal mandate cannot guarantee accessibility (or accountability for the lack of accessibility), given the power imbalances inherent to the carceral environment. This gap between the legal promise of menstrual supplies and its reality is its own form of structural violence that women are forced to close by purchasing additional menstrual products when available or by engaging in a sharing economy with their fellow prisoners.

In an interview with Jane Dorotik, a woman who spent 20 years in two California state prisons, she explained that women were allocated two menstrual pads per day of their cycle—but for some women it was often not enough. Cycles and flow vary woman to woman, causing some to need more than two pads per day, or even causing periods to be inconsistent, thereby the need for menstrual products would also be inconsistent. Pad distribution is, by this account, equal, but it is not equitable. Any woman who needed more than two pads could request more, but it was commonplace, Dorotik said, to be informed the prison was out of stock. If and when pads were available through the commissary, prices were often out of reach for women earning at the lower end of California’s prison wages. Without the means or the supply, women would turn to each other. Women would share with each other as needed (Jane Dorotik, personal communication, April 25, 2023), thereby creating informal economies of sharing and relying on their personal networks in order to meet their needs.

In this environment of limited resources despite legal mandates, an exaggeration of agency is created, in which choices and access to menstrual products that seem to be—and are promised to be—abundant, are in fact, not. According to Paul Farmer, structural violence, as the very DNA of the carceral environment, is a barrier to true personal agency (Farmer, 1999). Furthermore, Seth Holmes quotes Scheper-Hughes’s definition of ““everyday violence” to describe the normalized micro-interactional expressions of violence on domestic, delinquent, and institutional levels that produce a common sense of violence and humiliation” (Holmes, 2013). Everyday violence is built into the structural violence of prison.

Dorotik not only had strong familial connections on the outside, but came from middle-class means, which allowed her to navigate these conditions in a relatively privileged way. She was able to meet her basic needs while circumventing at least part of the restitution garnishment by having her family send her boxes of supplies rather than money. Her job in the law library was considered “good” and while her wages were garnished at the 50% rate, she wasn’t forced to budget the remaining 50% she was able to keep down to the penny (Jane Dorotik, personal communication, April 25, 2023). This allowed her to minimize how much money was contributing to the system, while gaining access to essentials. It was savvy, but Dorotik’s access to outside support is the exception, not the norm.

Progress?

That menstrual products are hard to come by despite their supposed mandate, underscores the rift between intention of changemakers and the impact felt by incarcerated populations. The legal mandate, however, does indicate recognition, in society’s most formal, “for-the-record” spheres, that the structural violence inherent in the carceral environment must be corrected. And in this way, California is more advanced than most. In the face of a monstrously-sized problem, where shutting the whole carceral system down—while tempting—is not realistic, issue-by-issue and state-by-state solutions are fundamentally changing the real life, day-to-day experiences of California’s incarcerated population in positive ways.

Take for example, the $6.40 monthly wage mentioned earlier. Up until 2019, a co-pay to visit the prison doctor would cost a person $5, thus leaving them with very few funds to carry them through the month otherwise. While a $5 copay sounds like a bargain on the outside, to people in prison it represented an exorbitant fee that led to tough decision making around how dire a health problem had to get before going to visit a doctor. Self-rationing healthcare is a costly move, both economically and physically, as it can lead to worsened health outcomes down the line, which in turn leads to the need for more involved and more costly care ((Prison Health Care: Costs and Quality, 2017)). In 2019, California deemed it unconstitutional to bill for copays in prison, stating that it violated an incarcerated person’s right to healthcare per the 8th amendment (Ruger et al., 2015). Notably, the $5 dollar figure was found not to be significantly meaningful to prison balance sheets, and therefore its cut wasn’t expected to hurt operating budgets. While true, the argument falls right in line with the existing forms of structural violence enacted against incarcerated people, implying that help and relief will only be possible if it doesn’t disrupt the powers that be.

Another example of progress fighting against both structural violence and the prison industrial complex is telephone calls. Without the internet, social media, email, texting, telephone calls remain one of the few lines of connection to friends, family, and community that incarcerated people have on the outside. Prisons are designed and built to prioritize security, thus in effect amplifying isolation and breeding loneliness. In May 2023, the US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy declared loneliness an epidemic that has terrible health effects from depression to stroke and heart disease, citing social disconnection as the cause (Nirappil, 2023). Loneliness has also been cited as having the equivalent health effect of smoking 15 cigarettes per day (Kidambi & Lee, 2020).

Like copays are a barrier to accessing care, charging for phone calls is similarly a barrier to accessing connection. In 2023, California Governor Gavin Newsom made it illegal to charge money for prison phone calls (California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 2022).

From Here On Out

In this piecemeal approach to deconstructing the structural violence facing incarcerated people, there are many issues of social suffering and inequitable distribution of healthcare resources that legal policy could tackle next. Since modern day prisons are a direct descendent of slavery (The Chains of Slavery Still Exist in Mass Incarceration, 2021), and slavery wiped out so much potential for generational wealth for Black Americans (Schermerhorn, 2019), correcting the economic levers that disenfranchise people within a system of disenfranchisement would be a good place to start.

At the very least, prison wages—which have not kept pace with inflation—should increase to meet the basic standards of wages on the outside, thereby not stacking an economic punishment upon the punishment already inherent in the loss of freedom. Furthermore, if the percentage garnished for restitution resembled a tax, just as on the outside, it would be far less than 50%, thus allowing incarcerated people to hold onto more of their earned and gifted income. Critics of this model would suggest the system can’t afford it, and would go broke and be forced to close.

As society begins to place more emphasis on whole-person health, understand the benefit of prevention, and not only connect the dots between out social conditions and our health and healthcare experiences, but also formalize those values in legal frameworks and healthcare delivery models, there is hope that those same forces will continue to dismantle the structural violence and social suffering incarcerated people are still surviving under.

#

The Intersection Of Innovation, Social Theory, and Care Delivery in Carceral Environments

Whether telemedicine can be effective in a carceral environment is at the heart of the tension between system administrators at San Quentin State Peniteniary and the people who purportedly benefit from it.

Introduction to Telemedicine and Structural Unwellness Behind Bars

This paper will examine issues of healthcare access within the US prison system, specifically the application of telemedicine services as a means to increase access to care, and by effect, health outcomes at San Quentin State Penitentiary in Northern California.

Outside of prison, telemedicine has been shown to be an effective tool to create more efficient means of delivering care by reducing wait times and increasing access to care across geographical boundaries. Delays in care cause irreparable damage, leading to infection, exacerbation of chronic illnesses, or death. Telemedicine offers the opportunity to reduce delays, connect resources such as relevant data or specialist care, conduct remote diagnostics, and reduce the costs associated with physical transport to outside clinics (Nash, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic played a significant role in accelerating the adoption of telemedicine, both in consumer uptake and in financial reimbursement models. A 2021 report from McKinsey notes a 38x increase in telemedicine adoption compared to pre-pandemic baseline levels (Bestsennyy et al., 2022). Telemedicine’s most effective manifestation is when it operates as part of a larger ecosystem in which the technology is defined primarily by its form-factor and operates in conjunction with real human interactions, real-time data, access to information, social support, and behavior change modalities, acting in interoperable harmony with other tech-based platforms such as electronic medical records, wearable devices, and digital health tools. In this ecosystem, telemedicine in and of itself is not the solution, but rather is a tool, a mechanism, used to augment care delivery and the experience of care. This is telemedicine in its most idealized form. Telemedicine is not a silver bullet. It cannot perform surgery or take an x-ray or MRI. It cannot replace real-life human connection or have bedside manner. But it can be especially effective at managing chronic conditions like diabetes, asthma, and hypertension—conditions which affect 6.6%, 11.7%, and 22.1%, respectively, as of 2016, of America’s incarcerated population (Wang, 2022). In a carceral environment, specifically within San Quentin, whether telemedicine can—by this definition—be effective or not is at the heart of tension between system administrators and the people who purportedly benefit from it. Can prison, a place of systemic subjugation, a system which benefits from inequities of power, facilitate telemedicine services in such a way as intended: to increase efficiencies and access to care, and by effect, health outcomes?

Prisons are not a care-based industry. They are a “punishment industry” (Bauer, 2019). They are in the business of maintaining—or possibly even growing—their power and influence. Whether public or private, a vast constellation of businesses operate in support of such an institution. “Corporations producing all kinds of goods—from buildings to electronic devices and hygiene products—and providing all kinds of services—from meals to therapy and healthcare—are now directly involved in the punishment business. That is to say, companies that one would assume are far removed from the work of state punishment have developed major stakes in the perpetuation of a prison system whose historical obsolescence is therefore that more more difficult to recognize (Davis, 2003). Corporations make profit from the existence of prisons, a relationship which perpetuates mutual benefit at the expense of a group of people under its control. In this respect, prisons and the “prison industrial complex” are forms of biopower.

The delivery of healthcare services is one expression of biopower. In prison, healthcare services are legally mandated, as stated by the “cruel and unusual” protection clause of the Eighth Amendment (U.S. Const. amend. viii). The amendment also qualifies that the quality of care be of a certain caliber in order to be deemed humane and sufficient. But the reality is quite different. Prisons are not medical facilities and do not come equipped with the requisite machinery, diagnostics, testing, imaging technology, or specialized staffing to deliver comprehensive or properly preventative care. It is well documented in the press and in legal proceedings that, as a result, unwellness, pain, illness, and even death, festers behind bars.

San Quentin—California’s oldest prison—is one such institution which has been subject to allegations of healthcare mismanagement and inhumane treatment over the years. As is the case when such allegations are taken to court and the prison is found in violation of their constitutional obligation, the prison must correct course. If this does not occur to the court’s liking, the prison is placed under a receivership—a third-party method of holding accountable a large institution responsible for the health and wellbeing of a vulnerable population. San Quentin was placed under a receivership (Associated Press, 2017). Rikers Island in New York is facing a receivership (Stroud, 2022). Alabama prisons went through a receivership in the 1970s (Jenkins, 1979)—it is not uncommon. For San Quentin, the receivership was the result of a 2001 lawsuit, the Plata v. Schwarzenegger case. In it, enhanced IT infrastructure was mandated, thus laying the groundwork for a tech-enabled future in which telemedicine and other connected health modalities will continue to play a prominent role. This investment represents an acknowledgement that tech infrastructure has become a central tenet of meeting the constitutional definition of protection against cruel and unusual punishment regarding healthcare.

In order to understand the true value of telemedicine within the carceral system, the conditions and ramifications of health and wellness behind bars must be examined. Acknowledging the social, structural, economic, historic, and political factors that convene to make the modern prison is a prerequisite to understanding how health care interventions, such as telemedicine, might play out. This paper will look at telemedicine through (1) the lens of social theory and suffering, in which the structural forces and physical environment informs the experience of disease; (2) abolition versus reformist approaches to healthcare, in which investments and innovations may still have abolitionist aims; and (3) the accompaniment principle and whether telemedicine provides a unique avenue to understand the conditions of prison or whether its form factor disqualifies it from being truly accompanying.

Social Theories and Suffering as Applied to Care Delivery in a Carceral Environment

Social suffering, a phrase coined by Arthur Kleinman and colleagues (Kleinman, 2010), to provide a framework for global health practices, is everywhere—including the carceral environment for which its inherent constraints make social suffering all the more palpable to those under its effect. Social suffering exists within a realm of social theories aimed at understanding the intersecting forces of power. The social theories, including the four pillars of social suffering, as applied to health care delivery in the carceral environment as follows:

(1) Unintended Consequences

“All social interventions have unintended consequences, some of which can be foreseen and prevented, whereas others cannot be predicted,” said Kleinman in a 2010 Lancet article (Kleinman, 2010). Prisons exist to function as a social intervention (to house people who’ve broken the law) with both intended and unintended consequences, foreseen and unforeseen. Prisons in the US were always intended to be a punishment (Davis, 2003), but the failing health of people incarcerated in those prisons could be seen as one of the institution's unforeseen consequences. The more that is discovered about the effects of the carceral environment on the human body, mind, and spirit, the more society has to reckon with the system's intended purpose and its consequential effects. Kleinman suggests that social interventions must be continually examined for their potential harmfulness and if enough harm is found, the intervention should be terminated. The question of ‘how much [harm] is enough?’ is one society has wrestled with in public spheres for generations. In prisons, enormous harm is being done. Diabetic prisoners die without their insulin (Levin & Sitthivong, 2022). Colon cancer screenings are delayed due to a rationing of resources (Brooks, 2022). Solitary confinement damages the brain and spirit forever (James & Vanko, 2021). Mothers give birth alone, their cries ignored by prison guards, bleeding out, to stillborn babies (Roh, 2022). And while there are efforts to terminate specific prisons, such as the shutting down of California prisons whose closures are cited as being due to overcrowding and exorbitant costs (Ahumada, 2022), while laudable for their outcome, aren’t pointing directly to the inhumanity of the social suffering associated with being locked up in the first place. A Pew Charitable Trust report from 2015 shows that California spent more than any other US state per prisoner on healthcare at $19,796 (Prison Health Care Costs and Quality, 2017), a figure that increased year over year prompting Governor Newsom to take action to close prisons because the state simply couldn’t afford to operate them at such a scale. Within a more reformist sphere, healthcare interventions within prisons are met with mixed results. Telemedicine, which has had such success on the outside and had good intentions on the inside, is not the preferred medium for provider visits among prisoners at San Quentin, according to Steve Brooks, a prisoner serving a life sentence. The pandemic green-lit “tele-everything,” he said, from court hearings to visits with his physician, the consequence of which are feelings of isolation and disconnection from other humans, especially from those whose role it is to be healers and foster connection in deeply personal matters related to health. Brooks said in his six years at San Quentin, he has never seen a doctor face-to-face—only nurses—and during video consultations, he is discouraged from seeking the routine screenings recommended for his race (Black) and age group (over 50). The combined effect, the consequences, of telemedicine implemented in a silo in a resource-poor setting, is a void of human connection and a feeling that the institution does not care about him. The antithesis to this consequence isn’t to terminate telemedicine necessarily, as Kleinman’s theory would suggest. Instead, it would be to seek opportunities for in-person visits and even models of accompaniment.

(2) Social Construction of Reality

The social construction of reality “holds that the real world, no matter its material basis, is also made over into socially and culturally legitimated ideas, practices, and things,” according to Kleinman (Kleinman, 2010). This theory plays out heavily as cultural relativism and as it relates to prisons, can fuel divisive attitudes on the outside about whether prisoners “deserve” the treatment they get while incarcerated. Should a serial rapist get access to a community support and education group to help manage his diabetes? Not everybody agrees that he should, citing the cause of his imprisonment as a metric for what kind of life he deserves once behind bars. “You go to prison as punishment, not for punishment,” said Dr. Salmaan Keshavjee in a Harvard College lecture (2022). The Norwegians, like Keshavjee, believe the removal from society is the punishment and no further punishing circumstances are inflicted on the prisoners. They call it the “Normality Principle” (Høidal, 2018). By contrast, the US, where prisons are the direct descendents of slavery (Davis, 2003), punishment is embedded into every aspect of the carceral experience. It is believed by many that prisoners do not deserve proper healthcare. If they are in prison, then they must have done something wrong, and they don’t deserve cancer screenings, healthy meals, or mental health treatment; they don’t deserve to be treated humanely, the logic goes. In reality, this form of judgment and subsequent behavior and policy is a social construction rather than a truth with material basis.

(3) Social Suffering

(a) Socioeconomic and sociopolitical conditions can cause disease (Kleinman 2010). Prisons, as environments of socioeconomic and sociopolitical strife, cause disease because prisons are, broadly speaking, stressful. The most recent example of this condition is from the COVID-19 pandemic, in which the overcrowding in San Quentin that long predated the pandemic got worse and contributed to the swift and deadly spread of the disease. Incarcerated people were five times more likely to contract COVID-19 than a non-incarcerated person (Saloner et al., 2020). In San Quentin, in the summer of 2020, men from another prison—the California Institution for Men, the institution with the highest COVID-19 cases nationally—were moved to San Quentin without proper testing or quarantining protocols, mixing housing accommodations of the new men with the existing men. COVID-19 hadn’t spread in San Quentin until this change, but after the new men arrived, the virus affected 2,600 prisoners and staff. Twenty-nine people died, making it the worst outbreak in the country at the time (Haines, 2022). This institutional mismanagement of housing protocol resulted in a lawsuit citing the violation of the eighth amendment protecting against cruel and unusual punishment and unlawful imprisonment (CBS San Francisco, 2021). Another example is the unintended consequence associated with telemedicine implementation. The vacuum left by the lack of real life human connection creates feelings of isolation and a culture in which prisoners believe nobody cares for them, nobody is looking out for them. Feelings of loneliness—in this manifestation or others commonly associated with being removed from society and known community networks—are extremely dangerous to a person’s health. A National Institute of Aging study found that loneliness affects the body in similar ways as would smoking fifteen cigarettes per day. Furthermore, studies report that stress acts on cells by shortening telomeres, resulting in “cellular aging and risk for heart disease, diabetes, and cancer” (Lu, 2014). The more stressful the condition, the more dangerous to a person’s health—and prisons are extremely stressful places to live.

(b) “Social institutions that are developed to respond to suffering can make suffering worse” (Kleinman, 2010). Prisons are designed to, under the promise of public safety, alleviate suffering for the society at large by removing certain people from free society. But this social intervention has in effect transferred the perceived suffering of society to the creation of actual suffering in prisons. The question of who suffers “worse” —society or the prisoners—is answered easily by acknowledging that the removal of a person’s agency, whether through social, economic, or political means, is always the most harmful form of power extraction (Farmer, 2006).

(c) Pain and suffering are not solely held by the person faced with the conditions of social suffering, but extends into the family and social network as well (Kleinman, 2010). Prisons are out of sight, out of mind, by design, often built and operated away from populated areas and often far from family members. This distance both enhances the isolation prisoners experience as well as reinforces the notion that carceral institutions are a separate entity—rather than a part of and product of—society. As such, it’s easy for society, especially those immediately unaffected by criminal justice, to lose sight of the goings on of both prison and the prison industrial complex. The feeling of being forgotten by the world contributes to a stressful living condition, which as noted earlier, affects the body on a cellular level, aging it prematurely and making it vulnerable to disease states it might not otherwise be. In the absence of in-person visits due to geographical distances or a global pandemic, telecommunication services play a role in helping to fill the void. As is the case with telemedicine, tele-based services are, in an idealized manifestation, not meant as a replacement for in-person, human connection, but to augment it under special circumstances.

For the vast majority of people, prison is not forever. Ninety-five percent of incarcerated people will get out of prison and become part of the general population again. In doing so, they will bring with them lived experiences, disease, and illness that affect the mind, body, and spirit. In this way, prisons and the conditions they endorse are society’s collective responsibility, if not on ethical grounds then surely on financial. Tax payers bear the cost of a carceral system that sends people home sicker than when they arrived, facing medical conditions that will again become the public’s responsibility through public health systems like Medicare and Medicaid. It is in the collective interest to care for people in prison, and yet it isn’t done.

(d) “The theory of social suffering collapses the historical distinction between what is a health problem and what is a social problem, by framing conditions that are both and that require both health and social policies'' (Kleinman, 2010). When the health outcomes of a social condition are so deeply determined by that social condition, the solution must be both specific and holistic, addressing the health and the social simultaneously. This is how investments in prison healthcare services can serve abolitionist aims, rather than perpetuating continual harm by upholding an exploitative system.

(4) Biopower

Biopower is a term used to explain the exploitation of power over other humans for financial profitability. In order to exist, prisons must exercise biopower; it is inherent to their operations. As noted earlier, prisons—even public ones—contract with private businesses in order to run their operations. Everything from meal service, to medical staffing, email communications, and laundry. This is the “prison industrial complex” and it runs on the fuel of biopower. An extension of this exploitation is the association people have with the experience, such as people who become biologically—meaning, medically—defined by the experiences—usually traumatic ones—in their lives. Imprisonment is newly being referred to as a Social Determinant of Health (Peterson & Brinkley-Rubinstein, 2021). And while this is apt—people often leave prison sicker than when they arrived—Social Determinants of Health are also conditions that affect the likelihood a person will become incarcerated in the first place.

Innovation and Investment in the Context of Abolition and Reform

One of the aims of this paper is to explore the gray zone between abolitionist and reformist approaches to health care delivery in prison and how telemedicine, as a reformist solution in its most perfect form, could have abolitionist aims. Abolition and reform—or incrementalism—are not necessarily in opposition. In fact, for many people, they are part of the same solution, in which abolition is the long-term goal and reform occurs in the interim. Modern day abolitionists seek a dramatic reduction in the number of prisons, a feat only possible if it occurs within a system of other changes related to policing and criminal justice that removes power from these institutions and places it in the hands of citizens or nonprofits instead (Keller, 2019). There is precedence for this. New York City has a model in which nonprofit groups augment the role of keeping the community safe and receive financial subsidies from the city to do so. While New York has successfully—arrests are down, safety is up—replaced traditional policing with a replacement model that works for them, there is not yet consensus about what a prison alternative looks like. Generally speaking though, prison alternatives include places for rehabilitation, healing, purpose in the truest sense of the words. One architecture firm in Oakland, California called Designing Justice + Designing Spaces is working to make this a reality. Their Center for Equity is a collaboration with the city of Atlanta to reimagine a central city jail into a healing center, and serves as an example of abolition in action (DJDS, 2021).

The abolition of prisons—meaning a divestment in existing systems and investment in reimagined systems—cannot happen overnight. It is, what Dr. Robert Lustig, would call a “generational shift,” in which a generation of people who hold certain ideas about how the world should operate die off, and a new generation with revised ideas, come into positions of influence. In the meantime, people in prison today are suffering. People in prison today need help, they need change, and they need it now. Critics argue that investing in health care services and innovations are antithetical to abolitionist endeavors. The real world does not operate in a binary state of moral absolutes. There are people suffering from disease in prison today and those people need pathways for care today (Farmer, 2013). Dr. Paul Farmer was famous for his steadfast commitment to healing when and where he could heal, for helping the person in front of him regardless of bureaucratic protocols. Steve Brooks needs a colonoscopy. He needs meals that don’t feature so many simple carbohydrates so he has a chance of eating his way out of the prediabetes danger zone. He needs to feel seen and heard by his doctors, and less alone in the care experience in San Quentin. Abolition may be ideal, but it is not practical in the short term. The barriers Steve Brooks faces on a daily basis are the barriers that can be addressed by reforms. Furthermore, the delays, healthcare and otherwise, associated with abolition could be considered a violation of the “do no harm” oath that physicians take. This is when reform can fill in the gaps. There are reforms which incrementally dismantle and there are reforms which will never take on the eventual destruction of prison as its aim. It’s not always obvious which reforms will function as aligned with abolitionist ideals and which will perpetuate the same system until they are already in play and outcomes begin to become available. This is the case with telemedicine in San Quentin and how the promise of telemedicine does not match its reality.

In 2001, a lawsuit was brought against the 33 adult prisons within the California’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitations citing a violation of the eighth amendment for subpar medical screenings, failure to provide in medical care, insufficient access to specialists, delays in response times to emergencies, incomplete medical records, incompetent medical staff, including a failure to recruit, and a deficiency in providing care management for chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma, hypertension, copd, and heart disease—all told, a very serious collection of grievances. Thirty-four people died under these conditions from preventable circumstances (Plata V. Schwarzenegger, n.d.). In 2002, the courts agreed to allow the state to make changes they deemed necessary to improve conditions, but a report three years later showed that conditions were as grim as ever. Among the changes the state was making during this period included increased staffing, the innovation equivalent of a “faster horse.” By this time, while not mainstream in society yet, other prisons were already being equipped with telemedicine infrastructure (Nash, 2021) —but not San Quentin. When, in 2006, a receivership was put in place, removing the state from control of fixing the problem, San Quentin had endured many years of medical services that were actually harmful. It was now the receiver's job to hold the institution accountable as well as implement the changes they weren’t making on their own. The most significant change made by the receiver was to invest in telehealth services. An influx of financial and structural investment of this kind is seemingly anti-abolitionist, and perhaps it was. Its stated intent, however, was to modernize existing systems for maximum efficient use of resources. The outcomes being reduced delays in access to physicians including specialists, interoperability between telemedicine consultations and electronic medical records, increased ability to manage chronic conditions, and access to medical staffing from around the country because professionals wouldn’t have to be geographically tethered to the Bay Area necessarily. This was its promise, and in this way it did seem to increase access to care and by effect, health outcomes. But there were unintended and unforeseen consequences, namely that telemedicine investments without investments in holistic solutioning was always doomed to fail. As Steve Brooks recounts, in prison, the pandemic green-lit the adoption of tele-everything from court hearings to doctors visits, an experience he describes as dehumanizing. As a result, telemedicine services as they’re operating in San Quentin today do not serve abolitionist or reformist aims—the latter least of which with the prisoner, the patient, in mind. It can be considered true that telemedicine has provided reform to staffing issues and financial bottom lines, but not so with patient experience. Telemedicine cannot function in its idealized form if forced to operate independent of a robust ecosystem.

Tensions Between Whether Accompaniment and Prison can Coexist

“To accompany someone is to go somewhere with him or her, to break bread together, to be present on a journey with a beginning and an end” (Farmer, 2011). In a prison environment, proven models of intervention, such as accompaniment, are, except for within the prison population itself, not possible. The segregated nature of prisons from the outside world means that the folks best equipped to deliver care are locked out. If telemedicine, as an innovation designed to reach across distances both literal and tk, is considered to be a way into the lived experience of patients, then it fails to function as such in a carceral environment, due to the limitations associated with only seeing the version of events presented through a fixed-point camera. But consider the role of the prison nurse, who delivers care in-person, in real time. Even they are not capable of acting in accompaniment, despite their proximity. They may share space during the appointment, but the appointment is time-bound and their shared space does not extend into mealtimes, recreation times, or downtime. They are limited by their working hours, as by the fact that nurses do not live in prison as prisoners do. And so alternative methods of reaching people in the carceral setting are sought after, often from the outside as is necessary, and often through the form of virtual connection. It may be better than nothing, as the 2006 San Quentin receivership indicates, but it is not accompaniment.

The dehumanization affect Steve Brooks recounts, is a function of the physical distance between him and his provider. Instead of air, there are screens. Instead of eye contact, there is a camera. Instead of body language and nuance, there is a frame. While telemedicine creates opportunities for, potentially, more visits, it does not increase the depth or meaningfulness of those visits necessarily.

In unique instances, accompaniment behind bars can occur. It is really only possible between a prisoner and another prisoner, two people who are sharing not only living space, culture, and conditions, but also systemic subjugation, in which one is in a caregiving role to the other. Cellmates might care for one another if one is ill, coming off addiction, suffers a chronic condition, or is even recovering from COVID-19. It’s a special relationship that is fueled by trust, compassion, and also necessity. The California Medical Facility in Vacaville houses the only prison hospice care program in the state in which a specialized medical unit trains prisoners as caregivers for the dying (Jaouad, 2018). Fernando Murillo spent the last five years of his sentence as a hospice caregiver, often spending hours well beyond the scope of his assigned shift with people, especially if he could sense they were near their end. He described the experience of accompanying people on their way out of this world and into the next as “transformational” (Murillo, 2023). As far as accompaniment behind bars goes, this is as close as it gets.

Concluding Thoughts on How Innovation, Social Theory,

and Care Delivery Intersect in a Correctional Setting

Scholarly review of the topic of telemedicine in a carceral setting to date has taken a quantified approach indicating the cost-benefit models associated with augmenting at least some in-person prison care with a virtual visit option (Khairat et al., 2021). This approach is furthermore glaringly institutionally-centric as it focuses exclusively on the system rather than on the experiences of prisoners themselves. The fact that most academic research to date has focused on the ROI of telemedicine in prison and what a time- and money-saver it is, meanwhile the people for whom telemedicine visits behind bars is a lived experience report inadequate experiences, indicates that the research is incomplete. In an under-resourced setting such as prison, it is not uncommon for experiences and conditions to also go under-reported. As Dr. Anne Becker indicated in a Harvard College lecture, just because the data isn’t present, does not mean the condition isn’t. The parameters for data collection are not necessarily appropriate to the culture of prison and thus does not capture the truth of the situation.

Telemedicine may be an efficient method for delivering care in terms of cost in the immediate billing cycle, but not in terms of the downstream costs of caring for someone with a chronic illness inside prison, nor the downstream effects of the costs associated with someone's illness once they are released back into society. These efficiencies come at the cost of human experience, dignity, and connection. An environment in which so much else has been taken, so much else stripped away, is reason to treat healthcare interactions with more empathy, more compassion, more connection—not less.

#

In Prison, Pregnant, and Overheating

Fans may be more performative, than substantive, as they allow prisons to say they have addressed the heat problem, but in fact fans only make prison hotter.

A high-consequence intersection of climate change and prenatal care behind bars

To stay cool, prisoners have been known to soak their clothes in water before dressing or to flood their cell floors with toilet water, said Lauren Johnson, a woman formerly incarcerated in Texas who is now a policy and advocacy strategist for the ACLU of Texas. Johnson gave birth to her son while in jail in 2004—a birth location that was both strategic and lucky. For Johnson the birthing protocol in jail was preferable to the one in prison so she agreed to her plea deal on the condition she would only be moved into a prison after she gave birth. “Most of the time” in jail she said, she was kept in temperature controlled environments, but once she gave birth and was moved to prison, the luxury of air conditioning was gone.

Johnson compared the prison intake process—in an area nicknamed the “dog pound” because of the chain link “cages” they were held in—to a convection oven, saying “I’m glad I wasn’t there pregnant.”

The summer of 2023 was the hottest on record worldwide and with rising temperatures comes adverse symptoms associated with heat exposure: rapid pulse, nausea, dizziness. For pregnant women in America’s prisons, heat can be especially problematic.

Pregnant women have long been advised to stay out of the heat. Excess temperatures can bring on adverse symptoms for anyone, but pregnant women are more likely to experience cardiac arrest, eclampsia, sepsis during labor and delivery. New research published in the Journal of the American Medical Association indicates that both long- and short-term heat exposure can affect mother and baby during labor and delivery more than originally understood. In fact, exposure to elevated heat for 30 days or more during a pregnancy increases the risk of severe maternal morbidity, a classification the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention characterizes as “near misses” with death.

Air conditioning in prison is scant, said Amite Dominick, founder of Texas Prison Community Advocates and the 85 To Stay Alive initiative. If it exists at all, it is often only installed where guards or visitors spend time, said Johnson, and not for the general population.

In prisons in Alabama, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Texas, and California, women are moved “immediately” into air conditioned housing quarters upon learning they are pregnant, said Erica Gerrity, founder of Ostera Institute, a non-profit that offers doula services in women’s prisons across the aforementioned states and five federal institutions too. Sometimes the prisoner doesn’t know she’s pregnant, she said, until a test is administered as a routine part of intake.

At the Julia Tutwiler Prison for Women in Alabama, where Ostera offers services, air conditioning only exists in the dorm room reserved for pregnant women. Meals are still served in too-hot dining halls which women access through walking down too-hot corridors.

Women arrive to prison at all stages of pregnancy, said Gerrity, from not knowing they’re pregnant to on the cusp of labor. Furthermore, their living or environmental conditions prior to incarceration can be unknown which in many parts of the country can mean unchecked heat exposure, putting them at risk for, as the new research would suggest, undue complications.

When it comes to prenatal health, Gerrity worries more about other environmental factors like toxic water or the lack of nutritional food, both of which contribute to a pregnant woman’s overall risk exposure. Rather than champion those causes outright, the role of doulas is to be present with the mother-to-be, to support her in whatever way she requires. Still, she notices patterns of problematic living conditions, the fixing of which could benefit everyone from guards, administrators, and visitors, to prisoners.

In her experience, Gerrity said, wardens do want new ideas, and sometimes she’ll make strategic suggestions to this effect. Using the toxic water example, she might offer to make a donation of a water filtration system: one to benefit the staff and guards and another to benefit the prisoners. Even though this is an example, it illustrates a valuable intervention tactic: appealing to the workforce.

The most effective interventions are to meet employers where they're at, said Dr. Ronda McCarthy, the National Medical Director for Medical Surveillance Services at Concentra, a network of occupational health providers headquartered in Texas. As someone who makes recommendations for implementing heat illness prevention programs, she often relies on the business case for how cooler temperatures can support staff retention and ultimately boost an organization’s bottom line. This logic applied within a prison environment has the compounding effect of not only being good for officers, but also good for prisoners, which, she said, is her ultimate goal.