How Not to Deliver Mental Health Care in Prison

Stories of Healing and Resilience

When Craig Stanland’s depression deepened to the point his suicidal ideation became actual planmaking, he knew he needed help. Stanland was incarcerated in upstate New York at Otisville Federal Prison Camp from August 2014 to November 2015 where, when he reached out to a psychiatrist, she handed him a flier titled, “Stress Management Strategies.” On it were tips like “have a relaxing bath,” “give yourself treats,” and even physical activity recommendations like chop wood or go swimming.

“We did not have a swimming pool,” Stanland said. “So I saw that [paper] and I felt it was like putting a bow on the fact that [to the psychiatrist] I was a nuisance.”

This advice, as it turns out, was published by a husband and wife doctor team in the UK who work for Interhealth, an organization that works with aid workers, not prisoners. Stanland is not sure how their advice sheet ended up at Otisville, but admits, “there's good stuff in here, minus the context of somebody being in prison.”

This mismatch between his expectation of help and the contextually-inappropriate care he was offered is echoed in prisons across the United States. “Prison is an acute stressor,” said Dr. Nicole Jackson, who is the Director of Autopsy and After Death Services at UW Medicine. “As soon as you enter, your health plummets—and it's chronic, so that stress is ongoing.”

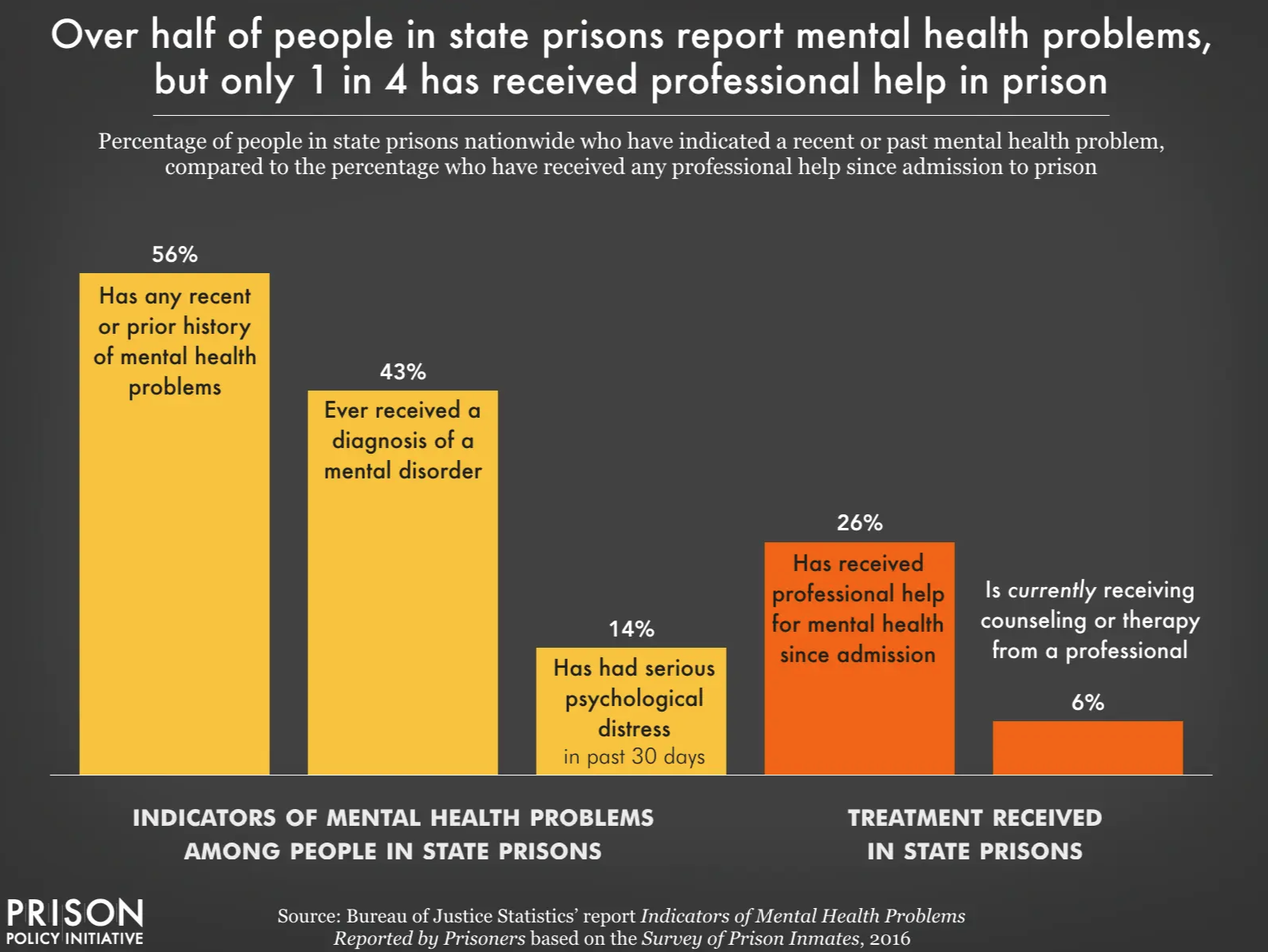

Over half of people incarcerated in state prisons suffer from a mental health condition, according to the Prison Policy Institute's reporting of the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ 2016 Survey of Prison Inmates (the most up to date data available). Yet only a quarter of prisoners report having received help. Six percent were currently receiving mental health care.

Prisoners are routinely let down by the very systems whose care they are entrusted to. While prisoners are the only group whose healthcare is constitutionally mandated—via the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the 8th Amendment—barriers to accessing that care are all too common, from appointment delays to lack of believability and outright negligence. In the absence of suitable, prison administered care pathways, many patients have developed their own coping mechanisms or tapped into holistic forms of care.

As a healing modality, yoga and meditation, for instance, makes a lot of sense to Oneika Mays, who taught an integrated practice of care at Rikers Island in New York for over a decade. Her teaching philosophy is tailored to the unique conditions of a carceral environment, she said. Yoga “is about this idea of connecting ourselves with the world around us and being able to calm the chatter that's in our minds, and using practices that are wrapped in unconditional friendliness. If that's not trauma informed, I don't know what is,” she said.

The five men featured here all served time, struggled with their mental health, and found healing despite the failures of the carceral system.

Craig Stanland

Incarcerated from August 2014-November 2015 in New York

Imprisonment meant losing his career, income, homes, and marriage, but worst of all, he said, he also lost his sense of self. “I was alone at rock bottom with the man who was responsible for this. And I loathed that man.” Stanland had begun to plan his own suicide when a friend came to visit him. His friend had driven over two hours to spend time together, a show of support that helped Stanland understand he is more than his mistakes. He was valued, and believing this helped him cope with his remaining time in prison. “I didn't even know that gratitude practice was a thing. I just sat down one day. The sunrise was absolutely stunning. And I wrote, I'm grateful I’m alive to see this morning.”

Beto Contreras

Incarcerated from 1991-2002, 2002-2006, 2009-2011, 2011-2013, 2013-2016 in Wisconsin

“What I've learned about the system is no matter where you're at, they pass out pills.” Contreras grew up in foster care and went to prison the first time at 16. He spent 23 years locked up, nearly a third of them in solitary confinement. On his seventh visit to solitary, something inside him shifted. “I was just so mad. I was like, “dude, you can't even be in population. You're in the hole again.” I looked in the mirror, and I really was sick with what I saw.” From that moment, he changed. He began working out with different people. He stayed out of highly-charged conversations and attended a group-style cognitive intervention program that helped course correct his internal dialogue. These efforts strengthened his spiritual connection to his mental health, something he has maintained since getting out. “It was hard,” he said. “But I did it.”

Colt White

Incarcerated since 2015 in Idaho, Texas, and Arizona

It’s not uncommon for prisoners to be moved from facility to facility, but White has also been moved from state to state—three times—effectively isolating him from everything he’d once known. While told the moves were due to his good behavior, he felt punished, and his resentment ate away at him. In Idaho, he had enjoyed working in a prison program that trains dogs. It gave him purpose. When he was transferred to a Texas prison that did not have a dog program, he was able to start one. Working with the dogs “shifted everything for me.” He said it’s scientifically established that “having a dog will lower your anxiety and decrease your blood pressure. It’s really healthy to have an animal.”

Mason Suehs

Incarcerated from 2008-2009 and 2017-2018 in Oregon

Suehs estimates he’s taken over thirty anxiety medications, usually two or three at once. “I felt like I was in a battle, you know, fighting my anxiousness all the time.” Other methods of relief seeking included meditating for two hours every day, not leaving his house, and reading self-help books. Still, he wound up in prison two separate times. One day during his second stint he heard other prisoners talking about The Insight Alliance, an outside organization that ran guided group meetings in the facility. The group’s underlying philosophy was just what Suehs needed to hear: you’re not broken. Thanks to the group, Suehs now sees his feelings as a kind of mental storm that flows through him rather than batters him. He doesn’t need to react or attach himself to every emotion. Today Suehs is a free man, off anxiety medication entirely, and returns to prison each week to lead the very meetings that changed his life.

Eric Clark

Incarcerated from 1992-2020 in California

Clark had so fully embodied the hardened criminal persona that he had to relearn how to smile, he said. His cheeks were sore for days. In Calipatria State Prison, in Southern California near the New Mexico border where Clark spent 14 years, mental health was highly stigmatized. People who displayed symptoms of conditions like ADHD or schizophrenia were considered weak—prey—and were beaten or even stabbed. This culture was exacerbated by the prison’s isolation both in geography and also from outside services—services like Boundless Freedom Project, for example, that offers meditation and yoga to some of California’s 34 correctional facilities. Clark’s first yoga class came much later, after he transferred to a new prison up north near Sacramento, a region with resources. He’d had hip pain due to nerve damage and a new doctor he was seeing, an Indian man, said he’s seen it before but the answer didn’t lie in Western medicine. The doctor told him to try yoga. Within a month, Clark could walk without a limp again, but it was the mind-body connection forming that really transformed him. “One of the things that yoga was doing was helping these brawny prison guys who thought all these muscles meant something learn that we were off balance between [the mind] and the rest of our bodies.” Yoga gave Clark clarity and helped him to understand he could make choices of his own volition, rather than what had always been prescribed to him by the culture he was subjected to. Today he works for the Boundless Freedom Project as a program administrator.

In sharing their experiences with what worked for their mental health and what didn’t, Stanland, Contreras, Suehs, White, and Clark are a representation of the knowledge and wisdom that could inform and reform mental health care services in prison. When formal systems fail the people they are purported to serve, those people suffer. The lesson then becomes, simply, to listen to those who’ve lived it.

#